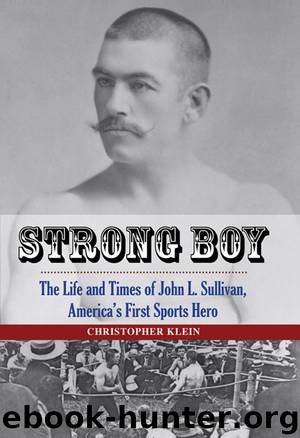

Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, America's First Sports Hero by Christopher Klein

Author:Christopher Klein

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Lyons Press

Published: 2013-10-04T16:00:00+00:00

The measure of any fighter is as black-and-white as the printed pages in the boxing record books: the wins, the losses, the knockouts, the opponents. Scan the bout-by-bout listings for the “Boston Strong Boy,” and one takeaway is crystal clear. John L. Sullivan never fought a black man.

The civil rights advances that had occurred in the United States in the decade following the Civil War and the abolition of slavery quickly eroded after the official end of Reconstruction in 1877. During the years of Sullivan’s championship reign, Jim Crow laws legalized segregation, white supremacists latched onto social Darwinism as proof of their superiority, and race relations spiraled into violence. Lynchings of blacks more than tripled from 49 in 1882 to 161 in 1892. Even the US Supreme Court upheld the separation of races in 1883 by declaring the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional.

The increasing institutional racism of the Gilded Age bled into the world of American sports. By the end of the 1880s, professional baseball barred African Americans from the diamond, a hardball segregation not to be broken until the Brooklyn Dodgers called up Jackie Robinson in 1947. Black jockeys had dominated horse racing in the decades following the Civil War—thirteen of the fifteen riders in the inaugural Kentucky Derby in 1875 were African American—but they began to be driven out of the sport in the 1890s.

Boxing, while not even close to being color-blind, was perhaps the most integrated sport—if not one of the most integrated segments of American society—in the late nineteenth century. Black and white fighters commonly met in the ring, although the crowds outside the ropes were almost purely white. The heavyweight championship, however, that symbol of physical prowess and dominance, was kept strictly in the grasp of white hands. The National Police Gazette offered a separate colored crown for black heavyweights. When Sullivan captured the heavyweight title, he felt a particular obligation to ensure that he would never yield it to an African American.

That pressure came in part from the Irish-American community that nurtured and supported him. Although many Irish immigrants personally experienced the sting of racism, they were among the most virulently racist groups toward African Americans after the Civil War. Following the abolition of slavery, Irish Americans found themselves battling against a new black labor pool for the manual jobs they had previously dominated. The competition bred antagonism.

John L. embodied the bigotry that flowed through Irish America. While he befriended black fighters such as featherweight George “Little Chocolate” Dixon, he didn’t want to associate with them in the workplace. “It wasn’t that I had any small grouch against the colored fighters, personally, because I like them,” Sullivan wrote in 1907, “but it was the race idea.” To John L., the color line wasn’t anything personal; it was strictly business.

Sullivan was not immune to the poisonous racism that infected most of nineteenth-century America, but as a hero who carried the banner of a city with a proud abolitionist past, he failed terribly in the chance to use his powerful platform to take a courageous stand.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Asia |

| Canadian | Europe |

| Holocaust | Latin America |

| Middle East | United States |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26579)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23057)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16837)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13282)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7098)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5482)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5069)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4783)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4782)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4441)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4333)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4235)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4167)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4076)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4009)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3936)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3620)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3449)